European Progress should be political

On September 26, the Swedish think tank Global Policy Research Group organized the first European Progress Conference in Brussels. The following are three short personal reflections on the event: What’s the right narrative for European Progress? Should European Progress be political? Are we dreaming big enough?

1. Blue pill or red pill?

Reviving European ambition. That’s the shared goal. But what’s the narrative to get there?

The conference organizers made the case for optimism, both in their manifesto and conference video. In spirit, it reminded me a bit of “things are better than most think” books like The Rational Optimist, Abundance, Factfulness, or Enlightenment Now. It’s better to live in Europe now than in 1950 or even 2000, and it’s better to live in Europe than most other places of the world. That’s true and still underrated! In a similar vein, if the goal is to motivate young Europeans to start ambitious start-ups, high-energy positivity seems like a good strategy.

And yet. Politically, a message of “Europe is doing better than you think” feels like a comforting “blue pill” that reinforces complacency within institutions and is unlikely to gain traction with voters. Everything is already good and will be better, so no need to change. Is this the right political narrative for a Europe which currently has the slowest economic growth of all regions and in which political parties that are discontent with the status quo are on the rise?

That’s why I like the “red pill”, the “Draghi pill”, which says Europe needs urgent reforms to strengthen its competitiveness, otherwise it is at risk of becoming significantly poorer relative to the US and China. When has the European Union managed to find a timely consensus across its 27 member states on reforms without a strong sense of urgency? Would the French “Giscardpunk” have happened without the “American Challenge”?

The challenge of European stagnation is too real for denialism. However, I empathize with the need to not only associate Europe with slow bureaucracy. A message of urgency and a celebration of European dynamism where it exists do not have to be mutually exclusive.

2. Should European Progress be political?

The organizers somewhat biased the event towards policy folks by choosing Brussels rather than a tech hub like London, Paris, or Zurich for the meeting. Still, I do think it makes sense for European Progress to have a political component.

First, I find it difficult for European Progress to be apolitical, given that Europe is also the ideological center of degrowth and given that the ambition of clean energy abundance is at odds with official plans.

On topics like metascience, capital access for start-ups, or e-government services it seems possible to change policies without being “political”. There is no ideology that explicitly opposes start-ups. Everyone can agree that having more European unicorns is desirable. So, the debate is mostly about how to achieve this.

Yet, Europe has political forces that explicitly advocate against abundance as a goal. Degrowth is the idea that rich countries should be “de-developed”. Jason Hickel defines it as “a planned reduction of energy and resource use designed to bring the economy back into balance with the living world in a way that reduces inequality and improves human wellbeing.” He argues that this material degrowth cannot be achieved with economic growth. Hence, he also instrumentally advocates for shrinking Western economies.

While economic degrowth remains a minority position, energy degrowth has become mainstream in Europe. European politicians have been telling their citizens things like it’s the “end of abundance”, we need “energy sobriety” and “saving energy, not using energy, is the cheapest energy”. This made sense in the context of the 2022 European energy crisis, where Europe needed to deal with a negative supply shock due to losing access to Russian gas. Yet, surprisingly, this is also the long-term plan of Europe.

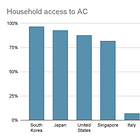

The EU has adopted a legally binding target to reduce final energy consumption by 15% from 893 Mtoe in 2023 to 763 Mtoe by 2030. Downstream from that there are national laws that force energy demand restrictions across the economy. In practice, this favors the continued deindustrialization of Europe with energy-intense industries moving to China, the US, and Turkey. And it doesn’t leave a lot of room for new energy demand from air conditioning, to datacenters, to direct air capture of carbon.

Second, many attendees at the European Progress conference seemed broadly supportive of European integration. A British participant brought an “EU Inc” hat. Another participant that I’ve talked to was a member of the federalist Volt party. People discussed making it easier for start-ups to reach scale in Europe and to cluster European STEM talent.

The traditional critique of Brussels red tape comes from the eurosceptical right. This vibe felt different. More “Brussels 2.0” than “Brussels bye bye”.

3. Are we dreaming big enough?

Despite being a conference aimed at reviving European ambition, the level of ambition was lower than in the US.

In SF houseparties people predict what year we’ll have a Dyson Sphere, in Europe we discuss which energy forms should count as renewable in the EU’s energy degrowth plan. In SF the labs aim to build superintelligence, in Europe the suggestion is to not try to compete on cloud or on foundation models and to instead focus on AI applications within industry verticals.

Even the Draghi report is surprisingly defeatist on cloud. As far as I can tell, the switch from CPU to GPU clouds coupled with NVIDIA’s preference to ship GPUs to clouds that don’t compete with it on the chip design layer has actually made the last years a good time for new entrants. CoreWeave was a crypto start-up with three datacenters when the AI boom started in 2022. Now it has a market cap of nearly 70 billion USD.

Maybe Europeans are more “realistic” and “serious”. Yet, I do think in Europe we are too quick to equate “I don’t know how to get there” with “it’s impossible to get there”. Imagine for a moment China would have taken this attitude: No sir, we can’t compete in mobile phones, cars, solar PV, batteries, or AI, the Americans and Europeans are too far ahead of us. The reasonable strategy is to double down on our existing advantages in textiles, bicycles, and toys.

Progress isn’t built in a day

European Progress remains a work in progress.

Happy to hear other hot takes and see you next time (or in SF)!

Indeed, I tried to get this mood across in my session but most people just don't pick up on the urgency and rather discuss the advancement of the idealistic European project (which I stand behind 200%). It's like "short term we can't do much, we have to think long-term" but then wr miss all the opportunities for actual change in an effort to show integrity.

I'm not sure I'd call it lack of ambition though. Imo there's a pragmatism that's missing. Capital market integration will take 2 decades? Lol whatever, who's gonna make it happen in 2 years then? Should we compete on model layer, evals or hardware or is it all too late? Bruv, let's do all of it. We need to cook.

Brain drain and talent spreading? Ok, who's going to build out the campaign for Zurich?

Rather than waiting for consensus and permission, Europe needs more doers that push the boundaries of what's thought to be possible. That's less a question of ambition and more a questions of ethics/social acceptance.

As an American involved in the Progress movement, I admire your courage your courage to try to change Europe. I think us Americans will have to implement many policy reforms to keep long-term widely-shared economic growth going, but overall, I am optimistic even if the American Progress movement has little effect.

On the other hand, I am sorry to say that I am very pessimistic for Europe. I am a committed Euro-phile and lived there for three years. But I think European politicians are terrified of fundamental reform and are looking for any excuse to keep an unsustainable welfare going while Europe ages and economic growth stagnates.

In the short and medium-term, I think that Europe will have a very hard time implementing the necessary reforms as they will be very unpopular with voters.