Moore’s Policy Drift

What frontier AI governance can learn from the Wassenaar Arrangement's three zone diffusion model

One popular idea in AI governance is that large AI models at the frontier of capabilities should be more regulated than smaller, less capable AI models. What constitutes a frontier model? Ultimately, performance. However, the legal requirement of third party capability testing can itself depend on frontier AI status. So, legally, which AI model counts as “frontier AI” has largely been operationalized with thresholds of computing power used in AI training. Examples include:

EO 14110: Revoked US Executive Order that required reporting for AI models trained with more than 1026 FLOPS of compute, or 1023 FLOPS for AI models primarily trained on biological data.

EU AI Act: Defines AI models trained with more than 1025 FLOPS as general-purpose AI models with systemic risk.

SB 1047: Vetoed Californian bill that originally included a 1026 FLOPS training compute threshold for defining frontier AI.

Yet, compute-indexed frontier AI governance faces a challenge that I call “Moore’s Policy Drift”. If a policy remains fixed, while the socio-technical environment changes, the policy’s impact can change and it may become increasingly mismatched with its original intention. This is known as policy drift. For example, if the law stipulates a fixed 15 USD per hour minimum wage and there is inflation, the real minimum wage is lowered over time. Moore’s Policy Drift describes the changing impact of fixed-compute thresholds due to the continuous exponential growth of computing power as predicted by Moore’s Law (and Huang’s Law for AI hardware):

Cheaper AI models reach fixed compute thresholds: The costs for a given amount of computing power are decaying exponentially. So, an iPhone 15 may have enough computing power to reach export control thresholds from the 2000s that were meant to target supercomputers. Without updating, an AI compute threshold drifts from targeting frontier systems (e.g. top 1%) to targeting a broad swatch of systems (e.g. top 50%).

Enforcing controls on all systems with a fixed compute threshold gets harder: Controlling the diffusion of AI systems with a specific amount of compute becomes harder over time, as such AI systems become more abundant.

The good news is that Moore’s Policy Drift can be managed. AI governance has discovered the idea of governing through compute around 2022. However, compute governance is much older than this. Indeed, computers are a dual-use technology that has been subject to international export controls for 70+ years. So, it seems worth asking, how have export control arrangements managed Moore’s Policy Drift over the decades?

The Wassenaar Arrangement as an example of exponential international governance

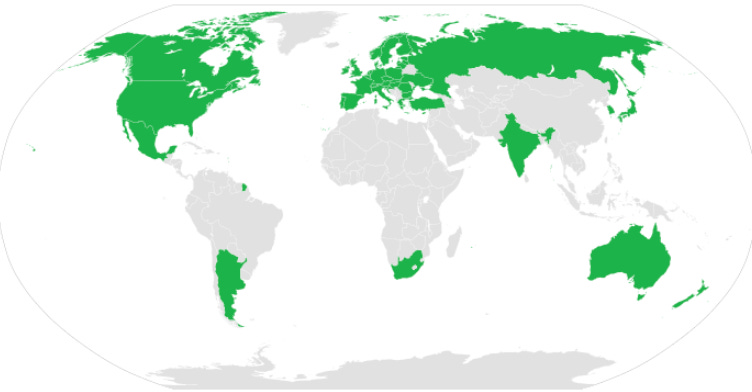

The Wassenaar Arrangement (1996-now) is one of the main current multilateral export control regimes for dual use technologies. The Wassenaar Arrangement includes the US, EU, Japan, UK, Russia, India, and Australia, and coordinates export controls vis-a-vis smaller “rogue states” like Iran and North Korea.

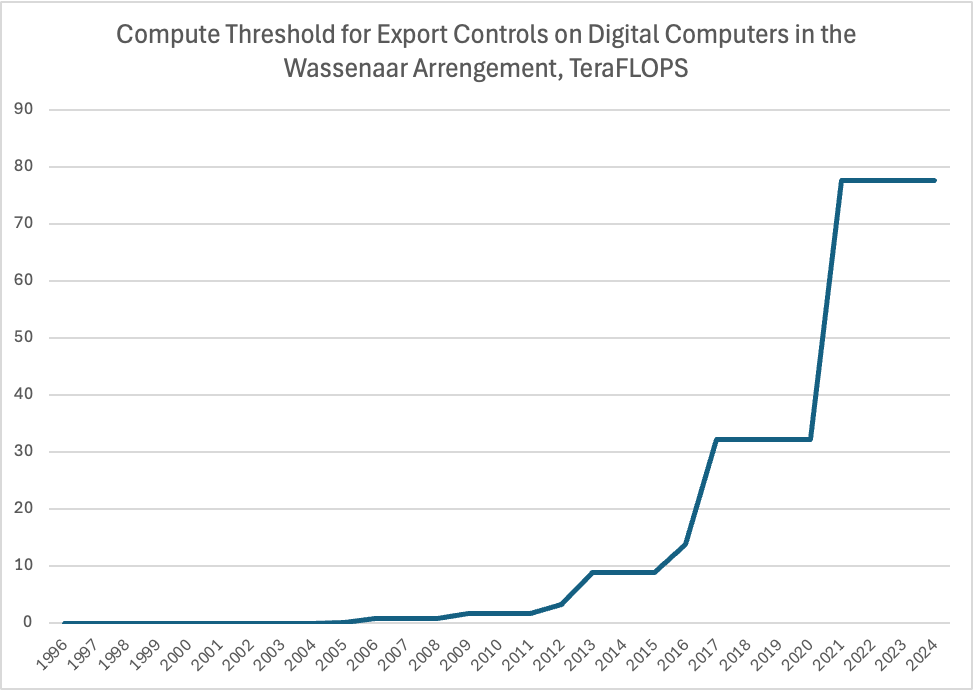

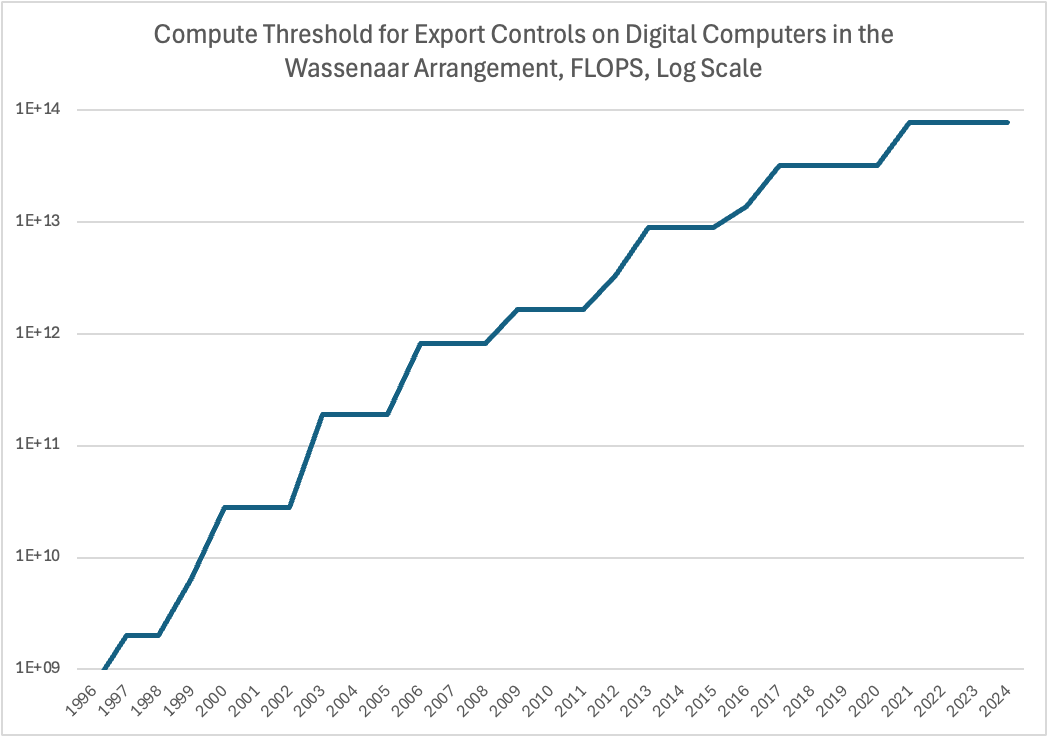

The Wassenaar Arrangement uses compute thresholds to define which computers are too advanced to be exported to rogue states without explicit permission. When we plot the thresholds on its control list in the last 30 years, we see the following pattern:

This may not look as smooth as Moore’s Law, but it clearly follows an exponential curve. We can confirm this by looking at the same data at a log scale:

On this exponential scale, the rise of compute thresholds for export controls looks pretty smooth. Over the nearly 30 years of the Wassenaar arrangement, the absolute compute threshold for export controls has risen by five orders of magnitude or about 10’000x. Which makes sense. The goal of Wassenaar is not to stop the absolute diffusion of computing power. It is to keep the free world at a relative advantage.

The updates of compute thresholds are not automatic. Rather, the plenary of the Wassenaar Arrangement meets once per year, often in December. Delegations from all Participating States attend and review control lists. Decisions are usually made by consensus. Consensus between 42 countries doesn’t sound like the most dynamic possible arrangement. Yet, this annual review has been sufficient for keeping up with Moore’s Policy Drift.

So, the Wassenaar Arrangement as an example of “exponential international governance” should make us bullish for the feasibility of compute-indexed frontier AI governance.

Compute-indexing vs. cost-indexing

An alternative to manage Moore’s Policy Drift would be to express thresholds for frontier AI in dollars (or energy). Given that the amount of compute available for a specific amount of money (or energy) increases exponentially over time this automatically adjusts the absolute compute threshold upwards. For example, after pushback that the fixed 1026 FLOPS threshold in the SB 1047 bill would lead to a growing set of models defined as frontier AI over time, this was changed to cost-indexing, with the threshold set at 3*1025 FLOPS + 10 million+ USD training costs or 100 million+ USD training costs.

However, it’s not obvious to me that cost-indexing should be preferred to compute-indexing combined with regular review:

Cost-indexing doesn’t fully avoid policy drift: The amount of money invested into computing power has been changing over time. Cost-indexed or energy-indexed thresholds would still require occasional review

More complexity: With cost-indexing, whether AI hardware or an AI model is covered by a regulation indirectly depends on factors such as how much money the FED prints (if not inflation-adjusted) or the composition of the FED’s consumer basket (if inflation-adjusted).

More shenanigans: The further we go away from measuring what we actually care about, the more we invite Goodhart’s Law to do its thing. For example, there is no global market price for AI cloud compute and a cost-indexed international agreement on frontier AI would favor AI producers from countries with low electricity prices or hidden compute subsidies.

Managed diffusion vs. non-proliferation

The history of compute governance offers simple lessons for compute-indexed frontier AI governance: Moore’s Policy Drift means that a regular review of absolute compute thresholds is necessary. A yearly review of absolute compute thresholds is sufficient to target frontier systems.

A focus on frontier AI approach can help to maintain a relative edge and ensure an early warning on emerging risks coming down the road. However, we should also be clear that Moore’s Policy Drift makes non-proliferation in a traditional sense (e.g. keeping countries from getting nuclear weapons) very difficult. Systems with a specific amount of compute become more abundant over time. On top of that, algorithmic progress also increases the capabilities of AI trained with the same amount of compute over time. So, stopping the proliferation of absolute AI capabilities without stopping Moore’s Law is very difficult.

The historical approach to compute governance as embodied by Wassenaar is managed diffusion not non-proliferation.

A three-zone model for managed diffusion

Managed diffusion faces another challenge. If participating states in an export control regime only limit the diffusion of digital computers, they would create a protected market for producers of digital computers in targeted countries. If the targeted countries have a large market, these producers may eventually become global competitors to the producers of participating states.

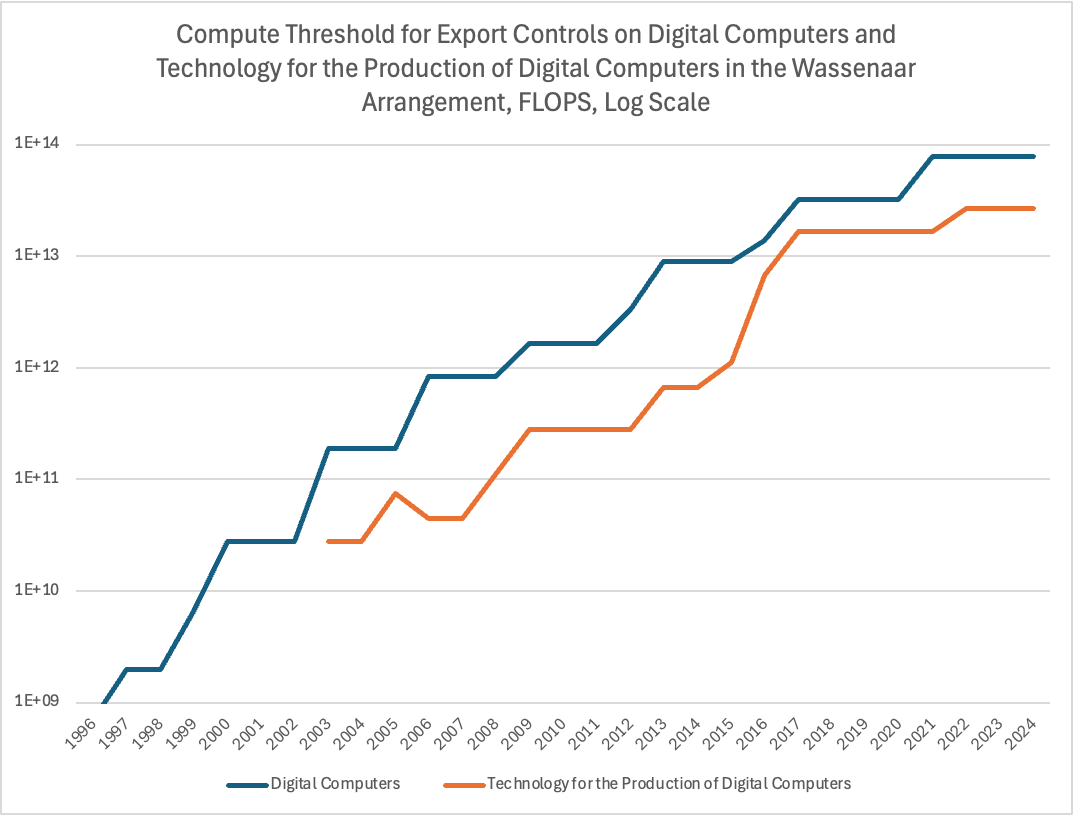

That’s why managed diffusion should happen at two layers simultaneously: The production equipment layer as well as on the final product layer. If we look again at our example of the Wassenaar Arrangement we find that it also has exponential export controls on technology designed to produce digital computers with a certain amount of computing power.

In the end, this creates an export control regime with three zones for managing frontier technology diffusion:

Frontier: The first zone above the blue line is one of frontier technology denial.

Buffer: The second zone, the buffer zone between the blue and orange lines, is a mix of permitted final product diffusion combined with production technology denial. This helps to ensure that producers of participating states still outcompete producers in targeted states despite export controls

Open diffusion: The third zone below the orange line is one of permitted diffusion behind the frontier.

Thanks to Andrew Miller & Jeff Fong for valuable feedback on a draft of this essay. All opinions and mistakes are mine.