The case against a decisive strategic advantage from superintelligence

Brodie vs. Bostrom

In his bestseller “Superintelligence” (2014) the philosopher Nick Bostrom argues that due to recursive self-improvement the leading AI project will likely gain a “decisive strategic advantage” over all other political forces, akin to the nuclear monopoly of the US in 1945. This project could then use that advantage to create a global government, for which Bostrom invented the term “singleton”. The two highlighted pathways to arrive there are a world war of choice to destroy all other powers or using the threat of war to peacefully create a global government with a superintelligence monopoly.1

At the same time, a superintelligence developed in 2044 within the context of an already existing mature logic of mutually assured destruction is not the same as a superintelligence developed in 1944. Bostrom’s idea of a “decisive strategic advantage” can only be true if it invalidates the theory of the nuclear revolution, first formulated by Bernard Brodie in “The Absolute Weapon” (1946). This is the idea that with nuclear weapons humanity has reached the ability to create such destructive technologies that wars between great powers are not “winnable” anymore.

Yet, Bostrom does not explicitly address the deterrence logic established by Brodie and explain why it doesn’t matter anymore in the future. I will make the argument that Brodie is in fact still relevant, even in an AGI world.

To be precise, I find it plausible that:

There are feedback loops between reaching higher levels of AGI and AI chip design, algorithmic AI progress, and better synthetic training data.

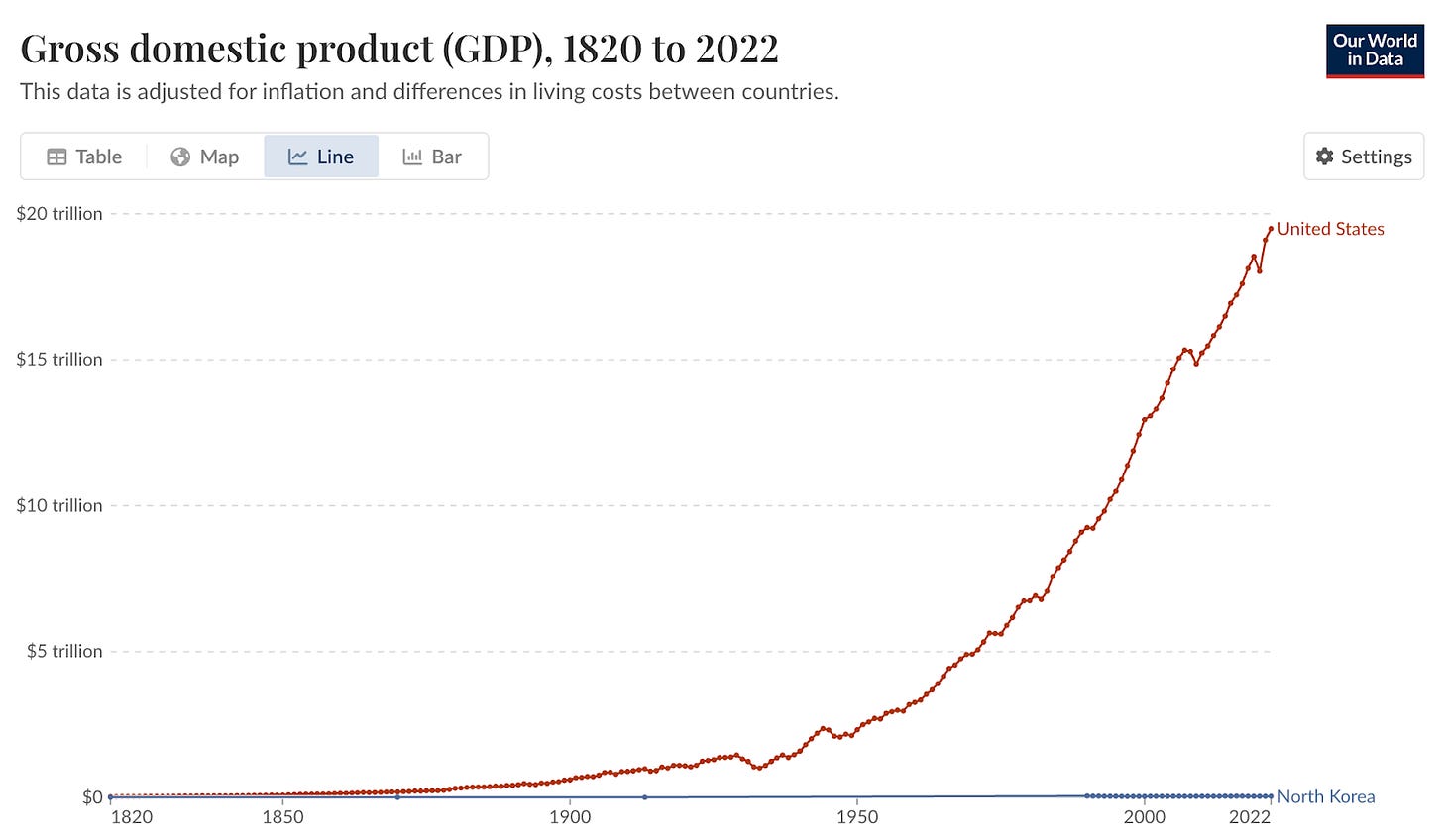

AGI raises the US and Chinese shares of global GDP

AGI gives a conventional military advantage to leading countries

Concerns about AGI may lead to more asymmetric countervalue deterrence strategies

AGI instances will become autonomous economic actors over time

AGIs may eventually form new sovereign entities with military power

I find it much less plausible that:

superintelligence makes wars between existing great powers “winnable” again

the first power to develop AGI can create or should try to create a global dictatorship

So, that’s what I’m arguing against. There is too much uncertainty to claim that a “decisive strategic advantage” is impossible. However, based on the available evidence it is at least unlikely. On top of that, the narrative that we should expect a “decisive strategic advantage” from AI is also normatively undesirable as it is destabilizing and increases the chances of a catastrophic war between great powers.

I explain my reasoning in ten stylized statements.

1. AGI has no inherent offense-defense balance

A number of AI experts have written about the impact of AI on the military offense-defense balance. However, the focus on whether a technology has an inherent offense-defense balance that either favors the attacker (and therefore wars of choice) or the defender (and therefore peace) can be a bit misleading. Historically, the offense-defense balance between states has arguably been shaped more significantly by technology diffusion patterns, by countervalue strategies, and by how third parties enforce norms against coups and wars of aggression.

a) Diffusion

It’s tempting to confuse the offensive advantage provided by having better access to a technology with that technology having characteristics that inherently favor offense if diffusion were equal. Daniel Headrick has extensively covered the role of technology from steamboats, to railways, to quinine, to telegraph, to machine guns, to air planes in enabling second wave imperialism, giving Europeans the offensive advantage. However, Headrick also shows that once diffused, this offense advantage usually dissipated. For example, the impact of the machine gun appears “offense dominant” in the unequally diffused Battle of Omdurman (1898), but defense dominant in the mature case of the Battle of the Somme (1916). AI can be viewed as an extension of the Revolution in Military Affairs that has been theorized since the 1980s and that has emphasized advanced scouting capabilities coupled with precision strikes. The U.S. military’s dominance in conflicts in the 1990s and early 2000s made it tempting to think of this new reconnaissance-strike complex as offense-dominant. However, these wars were fought by the world’s only superpower against small powers and non-state actors. The diffused precision warfare regime looks different. In Ukraine where both sides have established a tactical reconnaissance-strike complex we have seen a transparent battlefield with fairly static front lines. Or rather, the front line has dissolved into a much wider grey zone or “no man’s land”. Any large force concentration within this zone is vulnerable, making large-scale offensives challenging.

b) Countervalue

The nuclear age is not an age of inherent technological defense dominance. It’s about as much the opposite as it can be. In an all out conflict between two nuclear powers the biggest military installations and the industrial capacity of the defender can be turned into a burning, hellish wastescape within a few minutes. You may be able to stop some attackers, but you’ll never be able to stop all. In the words of Louis Ridenour (1946): “There Is No Defense”. And yet, we found a strategically stable solution in the form of mutually assured destruction. The logic is that you cannot win as a defender but you can still ensure that both sides lose. As long as some of the defender’s forces can survive a counterforce first strike, they can launch a second strike on countervalue targets. As long as it’s credible that they follow through, this is a price too high to pay for any would-be attacker.

c) Third parties

The global political order is semi-anarchic, not fully anarchic, and that “semi-” can make a big difference. First, there are collective defense arrangements that protect weaker states from aggression (e.g. NATO). Second, there is a normative element, where over the last 100 years or so, we have gradually managed to remove wars and coups as normalized elements of statecraft. This means an aggressor has to expect sanctions or other punitive measures even in the absence of collective defense. This has been a core element of a defense dominant world.

So, the question is what diffusion pattern of AGI should we expect and whether this upends the logic of the Nuclear Revolution and the broader logic of countervalue-based deterrence that provides strategic stability between great powers.

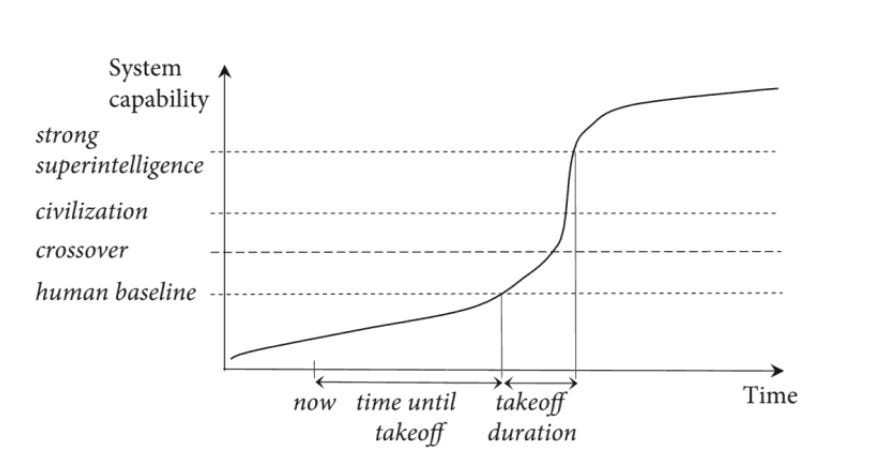

2. A fast take-off as defined by Bostrom seems highly unlikely

The take-off duration as defined by Bostrom is the time between human-level AI (AGI) and a strong superintelligence that is vastly superior to all of human civilization and that is near the limit of what is physically possible in terms of intelligence.

A fast take-off as defined by Bostrom takes on the order of “minutes, hours, or days”.2 As Bostrom argues in such a scenario likely no-one would even notice the intelligence explosion had taken place until the AI has already taken over. Bostrom argued that such a fast take-off might be possible due to a hardware overhang, in which much more AI hardware is available than needed to implement the software of human-level AI. This is also reflected in his note that any AI researcher with a personal computer may potentially start the fast take-off.

The toy model of a take-off put forward by Bostrom is pretty straightforward. Bostrom defined it as “Rate of change in intelligence = optimization power / recalcitrance”. Optimization power is defined as quality-weighted AI design effort and recalcitrance as the inverse of responsiveness to optimization power. He then assumes that “all the optimization power that is applied comes from the AI itself and that the AI applies all of its intelligence to the task of amplifying its own intelligence”. Lastly, he assumes that recalcitrance is constant (exponential curve) or that it falls over time (hyperbolic curve).3

In plain English, this assumes:

AI is at a single competence-level for all tasks

intelligence is the only input to improve the intelligence-level of the next generation of AI

intelligence-level scales (super-)linearly with intelligence input

There is good reason to be skeptical of these assumptions. I take the idea of feedback loops seriously, but they happen within an open, complex, adaptive system with constraining ecological dependencies.

It does appear that some feedback loops work. However, I would give a very low likelihood to an “intelligence explosion” timeline of days or weeks. For example, an advanced AI model running on AI chips may be able to create a design for more advanced AI chips. However, it wouldn’t be able to just self-replicate the chip on which it runs or be able to change its inherent chip limits like memory bandwidth or the number of tensor cores with software upgrades. For a new chip design to turn into more advanced AI chips that allows for more advanced AI models, it depends on a globalized chip supply chain with various types of giant, specialized machines. The time lag between a new chip design and the first customer shipment can easily be 1 year+. In fairness, Bostrom has argued that a fast take-off might be possible due to a hardware overhang, in which more AI hardware is already available than needed to implement the software of superintelligence.

However, even if we discard the need to upgrade AI hardware, there are other reasons to be skeptical of a fast take-off. For example, a large AI training run of the next generation of AI can still easily take multiple months. Similarly, something like getting feedback from the real world through experiments would still take time. And there are many practical challenges that complicate recursion from Amdahl’s Law to the fact that there is no perfect eval that can be maximized to maximize general intelligence to the risk of model collapse.

What Bostrom defines as a “moderate” or “slow” takeoff can still be very fast! However, as Bostrom himself admits: “If the takeoff is fast (completed over the course of hours, days or weeks) then it is unlikely that two independent projects would be taking off concurrently (...) If the takeoff is slow (stretching over many years or decades) then there could plausibly be multiple projects”.4

3. The cost of absolute AI capabilities decay exponentially, favoring AI diffusion

We can imagine different AI diffusion patterns. Still, I would highlight a few incentives that make it highly likely that we will see continued diffusion even as the technology gets more powerful.

Moore’s law + algorithmic progress + distillation: While the differences in national compute capacity ensure a relative AI divide in the scale of AI deployment, AI trends massively favor absolute capability diffusion. The costs of a given amount of AI compute are decaying exponentially. It requires less computing power to train and run AI models with an absolute capability level over time due to algorithmic progress and distillation of knowledge from larger models. The non-proliferation of absolute AI capabilities would require destroying most existing GPUs across the world, and then monopolizing all chip production capacity without smuggling.

Civilian AI market > military AI market: Computers were first a military technology, computer chips were first a military technology, computer networking was first a military technology. However, the civilian market potential for these general-purpose technologies is much bigger than the purely military market. That’s why the investment has flipped over to civilian dominance over time. The willingness of the US to engage in export controls & counterespionage was important. But so was avoiding overly militarizing computer technology and following a strategy of managed diffusion rather than absolute non-proliferation. The fact that the Soviet Union was much less open to domestic civilian use of computer networking has made it more difficult to create the demand and economic feedback loops for a healthy domestic industry. Similarly, AI clearly has military uses, but these are only a minority of overall uses.

Globalized supply chain: The current distribution of AI chips across the world is very uneven. However, except for the export controls on China, this is largely driven by market forces. It would be politically difficult to cut off chip access from allies that own crucial bottlenecks of the chip supply chain from Germany, to the Netherlands, to South Korea, to Japan. In some sense the globalized chip supply chain echoes the “Schuman Plan”, the defense-industrial European integration that started with coal and steel, extended to aviation and missiles, and that made war between European powers materially impractical. Whereas the export controls on China clearly have an effect, their enforcement is not perfect and their maximum severity has mitigating factors ranging from rare earths to the feasibility of blockading or invading Taiwan.

Natural planetary energy distribution: If AI is transformative enough to merit a very aggressive datacenter buildout then energy may increasingly be the bottleneck in the future. If we look at factors such as distribution of solar photovoltaic power potential we see a case for long-term geographic dispersion.

So, the question that I’ll try to answer with the following points is not “What will be the offense-defense balance of AGI?”, nor “Would a great power have a decisive strategic advantage if it manages to monopolize all advanced AI chips & development?”. Rather the question is: “Does a great power with a greater number of more advanced AGIs have a decisive strategic advantage over a great power with fewer and less advanced AGIs?”

4. Intelligence is an enabler of, not a replacement for industrial capacity

Imagine you could design an economy from scratch to maximize your warfighting power. Would you allocate all your economy to datacenters? No. First, even if you only cared about datacenters you would still need a lot of supportive infrastructure to build and operate datacenters. Second, datacenters are not sufficient for military power. You’re now great at propaganda and cyberattacks but that’s about it. As soon as someone manages to cut the energy or the fiber from your datacenters you’re done. Having the industrial capacity to churn out all types of physical military goods from guns, to artillery shells, to drones, to tanks, to missiles, to fighter jets still matters.

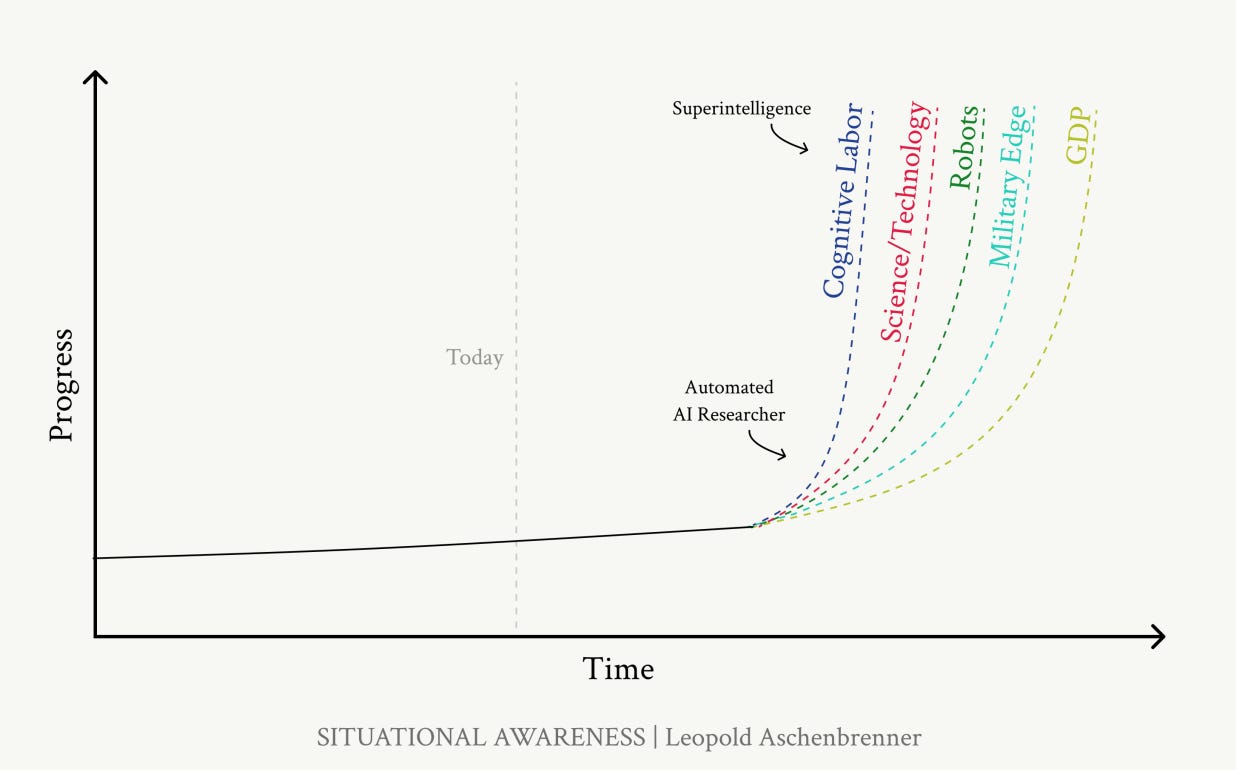

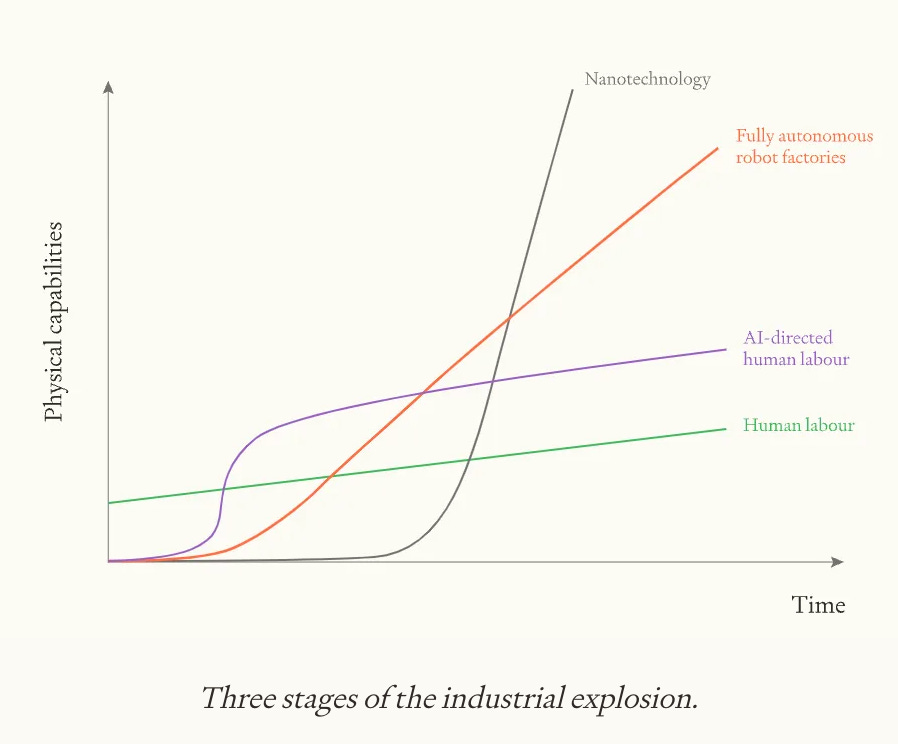

Now, a common assumption in Silicon Valley is that an “intelligence explosion” will shortly thereafter be followed by an “industrial explosion”.

So, am I being too nitpicky here, as whoever leads in AI automatically also leads in industrial capacity? My intuition is that the real-world is much more messy than the drawings above. So far, the evidence points towards a jagged frontier of intelligence and I would not expect this to be different for AI-enabled industrial capacity.

Second, the drawings above presume that human labor is the only bottleneck to industrial capacity and disregard other factors, such as the legal and regulatory environment. Ask yourself, is human labor the key bottleneck why San Francisco has so few skyscrapers? Would an army of Bob-the-builder-robots be sufficient to build the Californian high-speed rail?

Third, software arguably diffuses faster than industrial capacity. Open-weights AI models only lag about 3 to 12 months behind the leading closed models. I am not sure how to calculate the lag of the Western industrial capacity towards China from steel, to rare earths, to batteries, to solar PV, to the electricity grid, to robots, to UAVs, to shipbuilding, but I would guess it’s pretty hard to close that gap in a short time and that it would require enormous amounts of capex. So, it’s not that hard to imagine scenarios where intellectual breakthroughs may happen in the West but most of the production at scale happens in China. If you’re six months ahead in software, but six years behind in industrial capacity, you do not have a decisive strategic advantage.

5. Military innovation uptake speed is limited by acquisition cycles

“A little more than 10 years ago experts thought that what became known as the Revolution in Military Affairs would leave developing nations like ours incapable of opposing a high-tech power like the United States. With the help of The One Above, we proved them wrong. They were guilty, as those who defy the sayings of the divine usually are, of idolatry— though in this case they did not worship graven images, but the silicon chip. As though a speck of sand could defeat the will of The One Above. (...) Though the Americans claimed that information technology would allow them to get inside an enemy’s ‘decision loop,’ the irony was that we repeatedly got inside their ‘acquisition loop’ and deployed newer systems before they finished buying already obsolescent ones.”

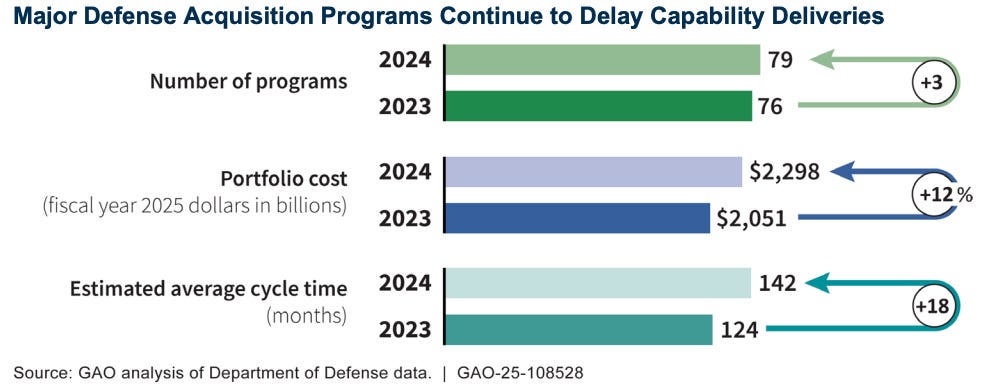

The ability of the military to field military innovations or to spin on civilian innovations is limited by the speed of acquisition cycles. On average it takes the US military about 12 years from program start to deliver even an initial operational capability. If anything, according to the Government Accountability Office the average acquisition cycle seems to be getting slower.

The most important information technology for maintaining strategic stability between great powers is generally quite old. For example, the US Navy has long paid Microsoft to keep its submarines running on Windows XP. More surprisingly, until recently, the U.S. Air Force’s Strategic Automated Command and Control System (SACCS) coordinated nuclear forces, such as intercontinental ballistic missiles and nuclear bombers using floppy disks. Legacy IT systems are not always bad, as military systems may prioritize reliability and stability over additional functionalities. Still, acquisition cycles are clearly much slower than the speed of IT development.

So, even if the US may have a theoretical lead in cutting edge technology, the US military may not always be the first actor to field that technology.

6. Frontier AI is kinetically vulnerable

If datacenters are relevant for the military balance, they will be targets in an armed conflict. That’s not hypothetical. For example, when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, it not only launched wiper malware and targeted Satellite internet, it also conducted kinetic strikes on Ukraine’s command, control, and communications.

Frontier AI is very resource intensive to train and still somewhat resource intensive to run for inference. The large datacenters required to train frontier AI models or to deploy them at scale require a lot of energy, they are immobile, and they are soft military targets. Even a facility that would qualify for the much vaunted “security level 5” has no active or passive defense against attacks with UAVs or missiles on it and its energy sources.

This vulnerability may be mitigated partially by:

Physical hardening: A few key military command data centers, such as NORAD’s Cheyenne Mountain Complex in the U.S. may be housed in bunkers under mountains.

Redundancy and geographic dispersion: AI can be deployed across many commercial datacenters in different regions. Key systems may have secure back-ups, similar to how Estonia has organized a backup of governmental databases in a “data embassy” in Luxembourg.

Mobility: For instance, Amazon offers a modular data center for the U.S. Department of Defense. This is a small mobile datacenter in a container with its own power and cooling, designed to be shipped by truck, rail, or military cargo plane.

Having some AI capacity that can survive a first strike seems desirable. At the same time, it’s also not bad that most current AI infrastructure remains militarily vulnerable in a conflict with a weaker AI power.

A secondary consequence of this vulnerability is that “frontier AI”, despite its name, would not be deployed at the front. Frontier AI may figure out strategies, battle management, and innovation somewhere far behind the front. However, on the battlefield where latency and jammable communications matter, I would expect smaller AIs on edge devices, such as on unmanned aerial vehicles, to make many decisions. Even far behind the front there is a question of how much concentrated compute would actually survive a war between near-peers. Given that the AI chip supply is highly internationalized with multiple very concentrated and hard to replace bottlenecks the flow of new state-of-the-art chips would likely collapse in a war between near-peers making high-tech losses hard to replace.

7. Adversarial warfighting tactics

One would think that the US armed with the most advanced weapons and the most powerful computer predictions from the Simulmatics Corporation would win against Vietnamese farmers in the jungle. One would think the only remaining superpower in the 2000s willing to spend trillions would triumph over illiterate goat shepherds in Afghanistan. One would think that the most powerful navy the world has ever seen would easily defeat a bunch of Houthis. Well, think again.

Military conflict is an adversarial affair and the opponent will try to force the fight into arenas where he can compete, from blending in with civilians, to terrain, to attacking soft targets, to public opinion. Technological superiority is an important advantage, but it “does not automatically guarantee victory on the battlefield, still less the negotiating table.”

Similarly, while it is conceivable that future AI will be more robust to adversarial examples, I would suspect that there may still be unexpected ways to defeat military AI systems that are superintelligent across most tasks. After AlphaGo it seemed obvious that the best Go programs would now forever be out of reach for humans. And yet, in 2023, a team of researchers developed adversarial attacks that would not work against a human opponent but with which they could reliably beat a superhuman Go program.

8. Asymmetric deterrence

The United States has a GDP about 1000x higher than that of North Korea. It’s roughly 30 trillion USD vs 30 billion USD. The US is not exactly a big fan of the North Korean government. However, North Korea has been able to deter the United States from a regime change by military force.

That’s the power of the “absolute weapon”.

Now, what happens if countries start to think their deterrent is not AI-proof?

The short-term answer is that it will make crisis postures more aggressive (launch on warning vs. retaliation after rideout). The mid-term answer is that countries will rely on more asymmetric, risky deterrence options. Most of us are blissfully unaware of how big the option space of alternative countervalue deterrence strategies is.

For example, as highlighted by about 50 years of the “war on drugs” it is difficult to prevent all smuggling of backpack-sized items across borders. What if you just packed a nuke in a backpack and smuggled it on a truck, cargo ship container, plane, or small boat across the border to a major city? This sounds pretty insane, but during the Cold War both the US and the Soviet Union appear to have produced hundreds such devices. If superintelligence threatens centralized nuclear command and control, the logical response would be to delegate and decentralize launch authority but that comes at the cost of escalation control.

It gets worse. The strategic stability provided by nuclear weapons reduces the incentives to pursue biological weapons. Biological weapons can be as destructive as nuclear weapons. “A hundred kilograms of anthrax spores would, in optimal atmospheric conditions, kill up to three million people in any of the densely populated metropolitan areas of the United States. A single SS-18 could wipe out the population of a city as large as New York.”5 However, bioweapons are less controllable and harder to track than nukes, which already do a sufficient deterrence job. This is ultimately how Matthew Meselson managed to convince Nixon to stop the US bioweapons program and to switch to international non-proliferation and counterproliferation efforts.

Would it be in the interest of the United States and humanity at large to push non-leading AI powers towards more asymmetric deterrence by countervalue options? Or to think these don’t matter anymore?

9. An unrestricted autonomy arms race between great powers may not be desirable due to loss of control

One might assume that any weapon that is very powerful must also have high military utility. However, as highlighted above this is not always the case. Militaries want to achieve objectives and the utility of a weapon depends on how suited it is to those objectives and what the alternatives are. Common factors beyond the damage potential of a weapon include speed, stealth, economic cost, political cost, and control. Militaries want to have escalation control and don’t unintentionally draw new actors into the conflict, hurt its own population, or create unnecessary collateral damage in the target country. For example, releasing a highly infectious disease on the enemy would be very risky as it’s very difficult to limit the damage radius.

When it comes to AI, many armed forces insist on meaningful human control over significant military decisions for legal and moral reasons. Given the unpredictability and brittleness of frontier AI this seems prudent. A famous cautionary example is that in 1983 Soviet early-warning systems falsely reported incoming U.S. nuclear missiles, but Stanislav Petrov suspected a computer glitch and chose not to relay the warning, thus averting a potential nuclear war. More generally, it can be in the interest of strategic competitors to avoid a red queen’s race, where both sides may end up with less strategic decision-time due to automation or even completely lose control over their AIs.

10. Uncertainty and human costs will persist

Maybe I’m underestimating how steep the AI feedback loops are, and maybe I just have a complete lack of imagination with regards to the “wonderweapons” that a future superintelligence may produce. Maybe one great power will suddenly develop the capability to secretly deploy a vast army of nanobots that can hide in the bloodstreams of targets without being detected and that can eliminate them at a moment’s notice. A Yudkowsky-style pager attack.

Maybe I’m underestimating how steep the AI feedback loops are, and maybe I just have a complete lack of imagination with regards to the “wonderweapons” that a future superintelligence may produce. Maybe one great power will suddenly develop the capability to secretly deploy a vast army of nanobots that can hide in the bloodstreams of targets without being detected and that can eliminate them at a moment’s notice. A Yudkowsky-style pager attack.

However, it’s at least worth highlighting that the history of wars is also a history of overconfidence. Is your army actually as capable as your generals or your AGI claims? Who is tricking whom in the intelligence game? “Three days” can turn into more than three years. “Over by Christmas” can turn into millions dying in rat-infested trenches over four years of attrition warfare. So, even if a power might be able to win a great power war with a first strike with reasonable losses on its own side, there will always be a level of uncertainty about this.

As a parable of caution: The 1991 Gulf War is *the* emblematic war of the Revolution in Military Affairs. The US-led coalition forces used cutting-edge technologies to achieve a swift victory over Iraq. Information Dominance. Network-centric warfare. Complete paradigm shift. However, even in this triumphant hour of the reconnaissance strike complex, the inside accounts paint a more murky picture. Behind the scenes, the US was very concerned about suspected Iraqi bioweapons (at that point the supply chain for botulinum toxin vaccines consisted of a single horse6). In January 1991 the US tried to take out the Iraqi bioweapons program with a series of airstrikes. The Defense Intelligence Agency reported that the US had taken out all known Iraqi facilities. However, as it later turned out the Iraqi program was much larger than the US thought and largely survived the war intact. Iraq did not use them due to the US threat of a nuclear response to a bioweapons attack and the goal to keep US war goals limited to freeing Kuwait rather than regime change. The actual destruction of Iraq’s bioweapons program only followed 1995-1998 in the context of the United Nations UNSCOM program.

Lastly, even if one side is able to win a great power war and confident that it can do so, this does by no means mean that one should start such a war. If you could click a button to kill a million humans in another country without repercussions, would you do it? I hope not! Except for very few circumstances, clicking such a button would be a deeply anti-human action. The population of other countries are moral patients too! Deterrence demands the iron determination to retaliate in a second strike. An all-out first strike during peace times is a morally very different beast.

The United States has neither started a “preventive” world war to defend its initial nuclear monopoly (1945-1949) nor has it tried to start a world war during a period of increased vulnerability of Soviet second strike forces, and this was the right decision.

Brodie can survive Bostrom

Bostrom’s book argues that due to feedback loops the first party to develop superintelligence will likely rule the Earth, if not the Universe. In contrast, I have argued that the situation is much more complex due to factors such as fast AI diffusion, the internationalized chip supply chain, non-intelligence industrial bottlenecks, military acquisition cycles, adversarial tactics, asymmetric deterrence options, and loss of control concerns. A decisive strategic advantage cannot be excluded as impossible. However, it does seem highly unlikely.

Beyond the empirical question there is also the normative question. Popular narratives about the future can feed back into reality. So should we promote the decisive strategic advantage scenario as a likely outcome for instrumental reasons? My answer is again no.

First, Bostrom’s “first past the post takes the Universe” thesis creates a giant premium on haste and is therefore instrumentally at odds with his own plea to be cautious and not race there. Second, the more AGI is perceived to undermine strategic stability, the more great powers that do not lead on AI will choose to go for more asymmetric countervalue deterrence, which is not desirable. Third, at the extreme, the perception that superintelligence could provide a “decisive strategic advantage” could foster armed conflict to prevent an AI monopoly or to defend an AI monopoly. Even a conventional war between great powers would have devastating consequences, a non-conventional war could end humanity.

In contrast, if we realize that there is no clear finishing line at which one party has “won”, there is more moral clarity. For better or worse, the great powers cannot easily get rid of each other. Open-ended strategic competition will persist. And so will the need to co-exist and to pragmatically show mutual restraint on destabilizing options like targeting nuclear command and control with cyberattacks.

When the US developed nuclear weapons in 1945, some philosophers like Bertrand Russell and generals demanded starting World War III to defend the nuclear monopoly. Many nuclear physicists, including Albert Einstein, demanded world government. And yet, it was Bernard Brodie that figured out 90% of nuclear strategy pretty much on his own in 1945-46. Brodie has been the intellectual foundation of the long peace and the world order of the last 80 years. His most famous line on wars between nuclear powers still rings true to me:

“Thus far the chief purpose of our military establishment has been to win wars. From now on its chief purpose must be to avert them.”

Thanks to Steve Newman and Andrew Burleson for valuable feedback on a draft of this essay. All opinions and mistakes are mine

Nick Bostrom. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, & Strategies. pp. 106 & 107

ibid p. 77

ibid pp. 79-94

ibid p. 95

Ken Alibek. (1999). Biohazard. p. 7

Fun sidenote: My memory was a bit hazy so I asked GPT-5 what that famous “cow” was that constituted the entire botulinum toxin vaccine supply chain during the first Gulf War. GPT-5 enthusiastically went with my suggestion and made up fake cow names from “Matilda”, to “Moozie”, to “Cow No. 6”, to “Moo”, to “One-eyed bessie”, to “Yvette”.

Couldn't agree more. This piece totally nails why Bostrom's superintelligence 'singleton' idea feels a bit off, especially when you think about how nuclear deterrence played out. I mean, with the sheer complexity and the distributed nature of AI development today, it's hard to imagine a single project maintaining that kind of tech leade without some serious counter-strategies emerging super fast.

Strong piece.

The deeper reason a “decisive strategic advantage” is unlikely isn’t just diffusion or deterrence, it’s that intelligence doesn’t dissolve coordination constraints.

Even superintelligence still has to operate through institutions, supply chains, command structures, and legitimacy. Power scales with organized coherence, not raw cognition.

Brodie survives Bostrom because coordination, not intelligence, is the true scarce variable.