We need to prepare for a post-labor economy

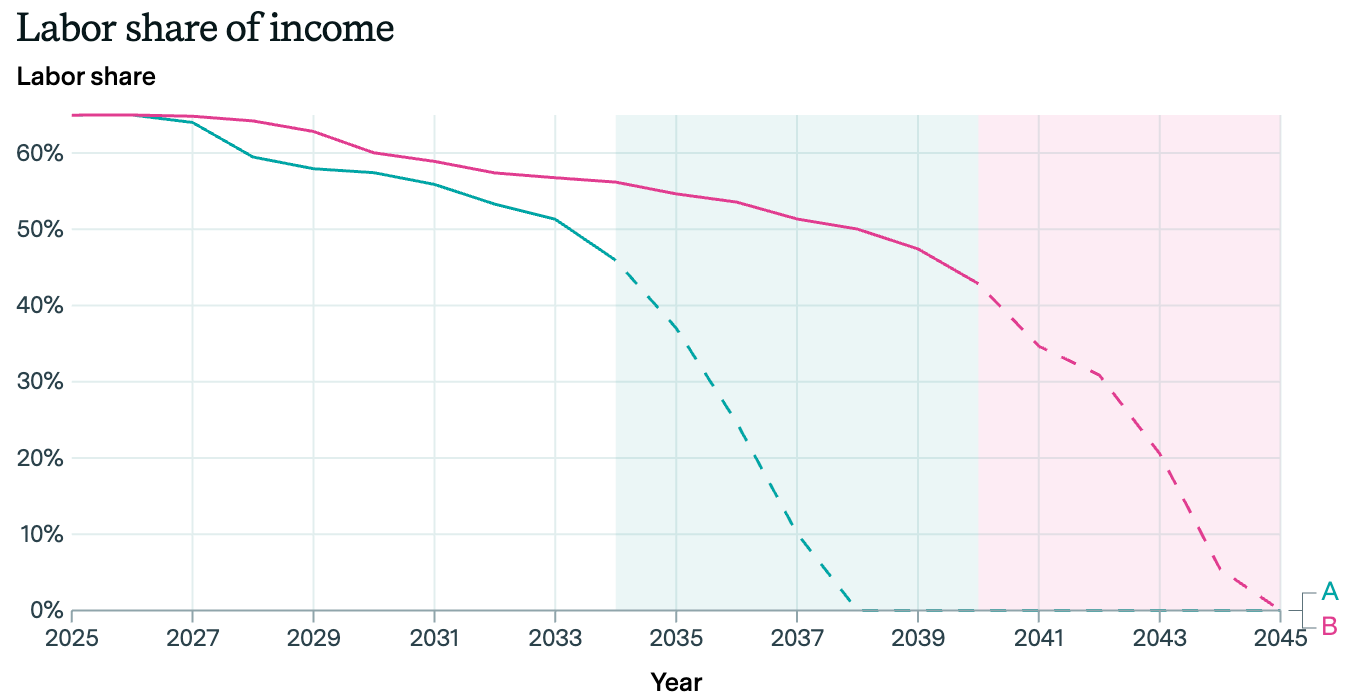

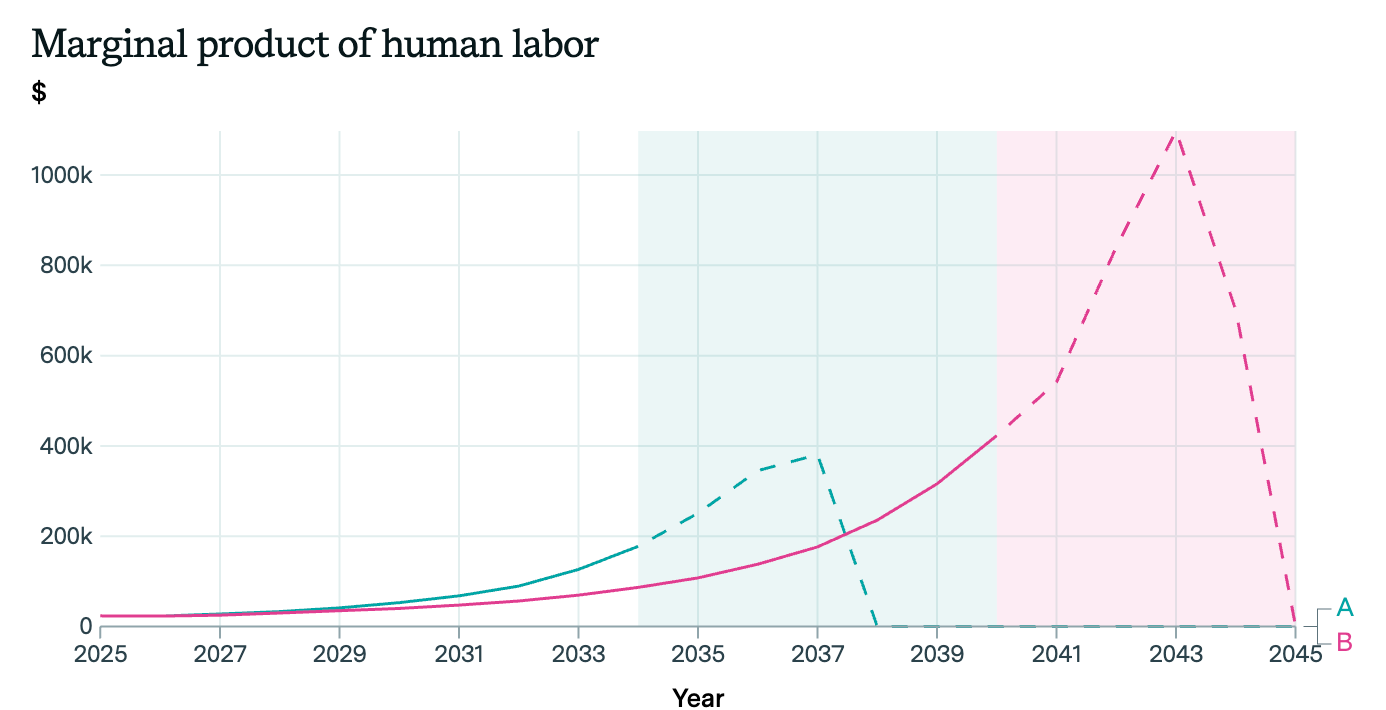

In March, EpochAI released an AI automation prediction model, which predicts rising wages for the near-term, but a rapidly declining labor share of income in the 2030s. In April, the AI Futures Project published a future scenario in which AI becomes superhuman at coding and AI R&D by 2027. A bit later, economist Tyler Cowen, known for his previous secular stagnation thesis, declared April 16, 2025 as “AGI day”.

Regardless of what particular threshold we accept as AGI, or by what year we expect a significant impact on the labor share of income, it does seem wise to start preparing for an “AGI economy”. The AGI economy blog series, which I started last August, is not finished yet, but it has covered some ground. So, it’s time for a mini-review. The goal has been to get beyond business-as-usual and beyond mere acceptance of a future AGI economy scenario but to work towards institutional solutions that make us better prepared for a transition from a labor to a post-labor economy.

Let’s speed-walk through it.

Thinking beyond business-as-usual

Many economists don’t expect a future with mass technological unemployment, AI that is significantly better than what we have today, explosive economic growth, or a need for policy measures beyond helping to retrain those that lose their jobs. In the short run, the business-as-usual scenario seems like a good bet. However, in the long run, it seems adventurous to believe that the integration of billions, then trillions of AI agents with general intelligence into the economy will not drastically change the labor market. The following are my responses to three prominent business-as-usual arguments:

a) Automation will be slower than expected

The history of previous automation scares, o-rings, jagged frontiers, the productivity paradox, Jevons paradox, Amdahl’s Law, Baumol’s cost disease, bank tellers, translators, radiologists, and truck drivers can be summarized in Hofstadter’s Law: it often takes longer than we expect. Even when technology would clearly be ready, it can take years or decades to deploy, due to legal hurdles, union resistance, and unclear regulations.

Response: Aside from maybe energy, I expect legal and social resistance to be the biggest bottleneck for the economic impact of AI in the coming decades. People will drag their feet and raise hell if there is no plan to distribute the benefits of automation. At the same time, as advanced AI increases the automation overhang to new heights, so does the advantage in economic competition to those societies that are able to reduce it. The democratic path towards a highly automated society must include a credible post-labor proof plan.

b) People that lose jobs, will find new, better jobs

We’ve automated away huge labor forces before. Most people once farmed for a living, yet modern economies still find new tasks for humans, from services to high-tech roles.

Response: Historically humans have had a unique advantage in learning new and complex tasks because they have had the highest general intelligence. Reasoning models will eventually be as good and then better than humans at learning new things.

c) Some jobs inherently require humans

People pay a premium for artisanal products like Swiss watches or French Champagne in part precisely because human labor makes them exclusive. Similarly, humans love to watch other humans compete in sports from chess to running to weightlifting, even though machines can outperform us in speed, strength, and game-playing accuracy.

Response: The labor share of income will not fall to zero in a post-labor economy. However, the appeal of many goods and experiences in this category boils down to social stratification within humanity. It’s not realistic or desirable to have a large share of the human workforce working on such goods and experiences.

Prediction is good, preparedness is better

A growing group of economists, including Robin Hanson, Erik Brynjolfsson, Chad Jones, Anton Korinek and the researchers at EpochAI, treat the potential for advanced machine intelligence to reshape the economy as a topic that deserves serious analysis.

Much of their discussion centers on three broad propositions:

AGI is possible/likely/imminent

Large-scale technological unemployment is possible/likely/imminent

AI-accelerated economic growth significantly beyond historical norms is possible/likely/imminent that

All three claims strike me as plausible, subject to the usual caveats about how one defines “AGI” and about the limits of analogies between the human brain and AI. Similarly, there is merit in raising awareness of such possibilities and making them more concrete through scenarios, predictions, and economic models.

At the same time, accepting the possibility/likelihood/imminence of business-as-unusual scenarios is the easy part. Let’s say you have persuaded an expert that “AGI by year X”, “take technological unemployment seriously” or “fast economic growth is possible”. What is the “so what” for economic policy?

Rather than predicting a specific timeline, the AGI economy series is an if-this-then-that analysis of solutions for a falling labor share of income. A falling share of labor income seems the most relevant indicator for a business-as-unusual scenario, because that’s when we need to go beyond the standard economic repertoire. In simple terms, it means that a lower share of the economy is used to pay human salaries. An economy in which less than half goes to pay for human labor, can be framed as a post-labor economy.

If the labor share of income falls steeply, absolute salaries paid to humans may decline as well.

In such a scenario, AI labor replaces human labor at a massive scale, and human labor increasingly lacks the bargaining power to profit from this automation. Instead we might see deflationary pressures on goods and services, as well as more income going towards legal entities with bargaining power in the provision of AI labor.

Solutions for the transition to a post-labor economy

Before we delve into the analysis of solutions for the “post-labor scenario”, it is good to be explicit about assumptions and normative choices:

Not fighting the scenario: There are measures that could be taken to strengthen labor and to postpone a potential drop in the labor share of income. However, that’s not the focus of this analysis.

Capitalism with AGI: There are post-capitalist economic future scenarios, such as fully automated luxury communism and the replacement of markets by a command economy run by a planetary scale AI. This series has only focused on a multipolar, market-based AI take-off as I consider this scenario to be underexplored compared to its likelihood. The scenario here is roughly that AGIs gain legal personhood and own capital, but that competitive markets persist.

Solidarity: There should be a minimum level of benefit sharing of AGI-driven growth to enable broad human flourishing across countries, cultures, and generations.

UBI is no quick-fix: A universal basic income (UBI) is worth pursuing, but it's not sufficient to manage the transition from a labor to a post-labor economy. Labor is a major factor in nearly every major aspect of our economic system. If the labor share of income falls, we also need a wider redesign of tax, pension, and social-insurance systems. If we only promise a massive expansion of social spending without scalable government revenues the government will go bankrupt.

Robustness across economic scenarios: The timeline of the economic impacts of AGI remains highly uncertain. We should initiate time-consuming institutional changes, such as tax reforms, sovereign wealth funds etc., now to be prepared in case of a near-term decrease in the labor share of income. At the same time, we should aim for solutions that are not harmful in case “business-as-usual” conditions continue for decades or longer.

Long-term resilience: If most future humans indefinitely depend on non-labor income, the system must survive asset crashes, corporate failures, and even national bankruptcies. Otherwise the long-term attractor state of human wealth in a post-labor economy is zero.

The solutions that I have explored focus on mitigating a potential drop of the labor share of income by building up streams of capital-funded income at three levels of analysis: individual, national, and global. The advantage of such a three-tiered structure is that it has redundancies in case one layer fails and that it can account for different levels of solidarity. These capital income streams won’t be able to replace labor income immediately. However, hopefully they can scale with the machine economy and set us up for a smoother transition to a post-labor economy.

Individual preparedness

This about policies that incentivize individuals to own a small share of the profits from automation (esp. through the stock market), even as the transition to that economy may diminish the future value of their labor. Only depending on the government for a UBI in a post-labor economy creates a dangerous power concentration and dependency on the goodwill of politicians.

a) Diversifying middle class wealth from housing

The middle class has a large share of its wealth invested into single houses. This is a concentrated bet on continued or expanding local housing scarcity and a very non-AGI proof way of wealth management. Governments are indirectly encouraging this by making it cheaper to loan money for buying a house than for investing in other assets. Governments should at a minimum consider loan guarantee and tax deduction neutrality between investments in different asset classes, and allow citizens to diversify their existing investments through debt conversion strategies.

b) Encouraging stock ownership through private pension plans

Public pensions are usually a pay-as-you-go system, in which a part of the labor income of working generations is transferred to retirees. Countries that strongly depend on such systems should consider more openness to occupational pensions and individual retirement accounts. These are usually capital-funded, meaning an individual invests in assets over his/her work life and these assets later fund that person’s post-work phase. The pension system is the biggest existing lever for individual exposure to the stock market / machine economy.

National preparedness

This is about policies that ensure government revenues scale with the growth of the machine economy. Once government revenue is ensured, we can talk about a massive expansion of social spending through an UBI. However, the hard part is ensuring the revenue, not spending it.

a) Transition away from reliance on labor income taxes

We need to think about other ways than labor income to fund the government. Right now labor pays about 50% of OECD government revenue through personal income taxes and social security contributions. This revenue will decline if the labor share of income falls, while demand for social spending will go up. The most common proposal to future-proof taxes is a robot tax. However, as I highlight this would be much more complicated in practice than it sounds. Other alternatives might include value added taxes, corporate taxes, land, or wealth taxes.

b) Sovereign wealth funds

Sovereign wealth funds are investment funds owned by the government. Without controls they can become slush funds or tools for political interference. Following the Norwegian model with an independent fund that owns a small share of a large set of equities, sovereign wealth funds can be a market-friendly instrument for governments to own a share of the national and global economy, and thereby have exposure to economic growth from AI. Notably, sovereign wealth funds do not necessarily have to be backed by natural resources as in the Norwegian case. For example, sovereign wealth funds through money printing sounds absurd but is kind of a reality in Japan and Switzerland. Similarly, social security contributions to a sovereign wealth fund are a logical instrument to preserve the poverty‑insurance logic of a public minimum pension at the national level without pay-as-you-go dependency.

c) Preserving the ability to tax AI companies

While there is no legal difference in tax rates for digital and brick-and-mortar businesses, digital businesses have de facto been paying lower tax rates, because it’s easier for them to shift intellectual property and profits across borders for tax optimization. With the prospect of cross-border AI services, AI inventions, and AI-owned companies this already existing challenge could get considerably worse. Ongoing international efforts led by the OECD and G20, which, amongst other things, establish a global minimum corporate tax rate, are relevant to limit a race to the bottom between future “AI tax havens”.

Global preparedness

This is about policies that guarantee some benefit sharing at a global scale, ensuring that no one is left behind.

a) Windfall trust

The basic idea of a Windfall trust is a voluntary commitment of leading AGI labs to share their profits with the rest of humanity through a trust if they ever reach astronomical levels. Preferably, AGI companies would already share some equity to be held by such a trust on behalf of humanity today. This would be more credible than a pinky promise to share profits in the future.

b) Common heritage of mankind resources

An “AI Industrial Revolution” could lead to a stronger demand for natural resources and a better ability to exploit resources in remote locations. Legally, most natural resources on the international seabed and in outer space are the “common heritage of mankind” and belong to all of humanity. If we can ensure that humanity gets its share in the future exploitation of these gigantic resources this could provide a longterm global revenue. This revenue could be reinvested into a Norwegian style fund that could eventually make payouts to humanity.

Getting the “boring” stuff right

Silicon Valley “feels the AGI”. It tends to be less buzzed about more mundane things like international tax treaties, pension systems and monetary policy. Conversely, tax lawyers, pension officials and central bankers don’t take the prospect of a post-labor economy seriously. However, if we want to be prepared for an AGI economy we need both, the openness to the business-as-unusual scenario as well as an engagement with existing economic institutions. That’s what this series aims to contribute to.

Why would housing not be robust against AGI? If socialization and bespoke personal services become the only advantages that humans retain after labor becomes supplanted, then agglomeration effects should be large. People will pay a lot for proximity and convenience.

Unless you mean that it will only be robust in desirable cities, but that's already sort of the case.

How are businesses generating profits in a post-labor economy? Without humans with income to pay for goods/services, how will AGI technology generate a return? Is there research or essays on the impact of potential mass unemployment?